The Philosophy of Modern Song

Directed by Michael Almereyda, performed by André De Shields, Odessa Young, Meshell Ndegeocello, and a groovy band.

Bob Dylan’s newest publication The Philosophy of Modern Song was, for many, a dad gift. It features mostly mid-century love songs described by Dylan. The chapters consist of artistic in-world characterizations of the speaker and factual contextualization of the songs’ creation. Part truth, part fiction.

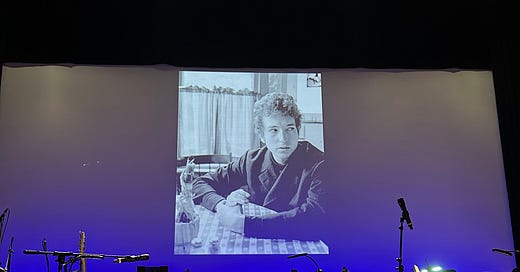

The songs of POMS were entirely inaccessible to me in silent reading. But in performance, words spoken and songs played, it made for a deeply enlightening experience. At the 92nd St Y, the band noodled over Mr. De Shields’ impassioned delivery of Bob’s words while a slideshow clicked by. The product was simple, moody. Through jazzy hypnotism, the elements of song, words, and visuals coalesced to put you into the shoes of someone about to burst into song. And then, the song. Theater did the material incredible justice. Mr. Almereyda created a more immersive experience than any Broadway show will sell you nowadays.

I now understand this book as a philosophy as I see that Bob Dylan is a philosopher. Many multi-hyphenates futilely try to transcend one prominent facet of their image; Bob actually does it. He eliminates any limits you might have on him. It’s insufficient to summarize him, just like it’s inefficient to call his songs Poetry. He’s the original “not into labels.”

His songs, like Shakespeare’s words, are also best not read on a page. He’s a performer like André De Shields is a performer. He embraces silence and expertly plays with timing. Mr. De Shields’ particular skill is getting every audience member on his side. The same side. He effortlessly charms with his grand presence. Both Dylan and De Shields demonstrate the value of paying due to your elders. Both are, in the best way, from another time.

Ms. Young provided the “factual” riffs on the song, where the story of its writing was revealed. That’s a simplification; at one point there’s a digression about Job from the Old Testament. Her accent seemed straight American until a rogue “oll” or “pawth” was spoken. I particularly liked when she did some business with a record player. After a song, she’d bring us back down to Earth. She had less textual flair to work with, but she, too, got the audience on her side.

At least 80% of the characters were braggadocios, hubristic men. I wondered if that kind of confidence is required for someone to earnestly pursue art.

I also wonder about this collection of songs: Detroit City, Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood, Strangers in the Night. Is Dylan drawn to them specifically, or is it just that the songs that are most riff-able? They avoid specificity and are therefore able to be projected onto. They’re also emotionally rich. It’s clear Dylan loves how vividly an emotion can be expressed through an ordinary moment.

The selection was quite small relative to the book, but the curation was sublime. My friend Harry Hew has a lot to say about Bob Dylan’s humor, and including the following line is an excellent example of using it well:

“Like any other piece of art, songs are not seeking to be understood. Art can be appreciated or interpreted but there is seldom anything to understand. Whether it’s Dogs Playing Poker or Mona Lisa’s smile, you gain nothing from understanding it.”

I chuckled at how defiantly Dylan, and the show, disproved this for me. I felt so enriched, so stimulated, so educated about life in understanding these songs I had no business otherwise knowing at all. More Dylan-isms that hit me hard: “What is it about lapsing into narration in a song that makes you think the singer is suddenly revealing the truth?” and “Context is everything.”

The songs were given beautiful arrangements by the five person band and Ms. Ndegeocello. Eyes closed, she oscillated between even, mellifluous tones and rhythmic spoken word. Another vocalist quietly riffed around her in tenor gospel. I felt the whole audience being affected, our brains attuned together to the songs. This has a name: collective effervescence. Live music can have this effect on people, as anyone who’s been to a contemporary church service can attest. The bookends of context made each song even more clear. I could understand the singer’s perspective each time, and catch the Easter eggs Bob had left us in the text. When the next song would be revealed, it would elicit an audible reaction from the audience. I gasped when a deep cut from “Babes In Arms” came on the screen. I couldn’t remember which musical it was from at first; I only heard a high school classmate’s voice singing it in my mind.

The production entranced me completely. It made me live in the communal moment. I could not want for more, though I did ponder how amusing it was to go to a musical Dylan event and not hear any Dylan music. And then they WHAMMED me with my FAVORITE DYLAN SONG OF ALL TIME, I’LL KEEP IT WITH MINE. I was so delighted for my unsung beloved to be given its due among its peers, masterful and deeply felt music. I choked up at the bounty. A statement that’s often echoed in Dylan fan communities: we are so lucky to be alive at the same time as Bob Dylan. We are so lucky to experience live music, thought, and philosophy.

Beautiful review. I hope they revive this event or take it on tour.

Ah ha that’s why you commented that a “Philosophy” written by you would have all female singers. You just saw this production! Awesome article - I wish I had been paying better attention I might have gone to that show. Great concept. Love that version of “Mine” too!